Across schools in the UK, primary school children are being subjected to a concept known as the ‘Zones of Regulation’. These Zones of Regulation are essentially a form of guidance for young children on how to control their emotions. This regulation of emotive responses is expected to be internalised and practiced by young children. As this article will show, these emotional controls are anything but innocent guidance for children and are located within a much wider system of ideology. Keep in mind that these controls are aimed at children as young as seven years old.

What is Self-Regulation?

Firstly, self-regulation is a way of composing the self within a given environment. It is a way of setting internal controls on behaviours which allow us to fuse or merge with a system in a way which conforms to the expectations of that system. To not self-regulate within a system or environment equates to a kind of deviance.

Of course, there are many different types of environments within which we self-regulate our behaviours and emotions. The self-regulation around dining etiquette is different to the self-regulation around a funeral which is different to the self-regulation at a heavy metal concert. It would certainly not be considered self-regulation if we were to start laughing during a church funeral service. However, would it be acceptable to cry at a funeral or would this be a lack of self-regulation of emotion?

The Zones of Regulation

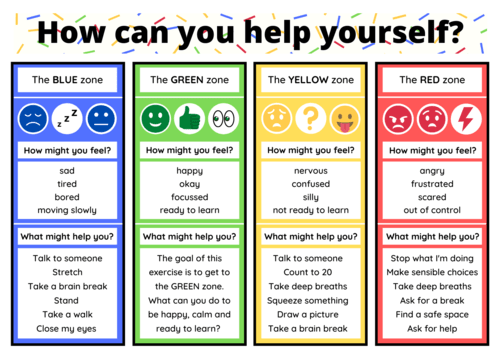

The Zones of Regulation was originally conceived by Leah Kuyper in her thesis with the notion of self-regulation of emotions in children as its main focus. The general idea is that emotions are sorted into ‘zones’ which consist of a blue zone for feeling sad or depressed; a green zone for feeling happy, calm, and willing to learn; a yellow zone for feeling anxious, silly, or confused; and a red zone for anger, frustration or fear.

It is apparent that the concept was originally targeted towards children with additional needs and who have difficulties in regulating their own behaviours. From the website:

The Zones of Regulation is a metacognitive framework for regulation and treatment approach that is based on immense evidence in the fields of autism, attention deficit disorders (ADD/HD), and social-emotional theories

The Zones of Regulation are often displayed in schools through child-friendly visual aids such as this one below which outlines in a simple to understand manner the various emotional states:

Kuyper is keen to express that each emotional state is perfectly okay to express and that the Zones of Regulation are not intended to be a compliance-based model. By ‘compliance-based model’, Kuyper means a model of self-regulation which complies with the demands of others. As Kelly Mahler frames it:

Essentially, a compliance-based model is repeatedly teaching ‘your body signals are not important–ignore them–hide them–what I think you should do is more important–and if you please me maybe I will give you a reward’

So, as far as the origins of the Zones of Regulation are concerned, it seems that intentions were genuinely humanitarian towards certain demographics when it came to formulating the system. However, rather than remaining targeted towards those with autism or ADHD, the zones are now being used in a blanket approach to behaviour for all children in settings where the zones are being utilised.

Little Neoliberals

One of the problems with this is that these actions have allowed the Zones of Regulation to be co-opted and subsumed into the wider ideological framework within which the Zones of Regulation are practiced. Alice Bradbury, professor of sociology of education at UCL, argues that primary school education in England is essentially designed to produce “little neoliberals”.

A central part of being a ‘little neoliberal’ is the requirement to self-regulate which, in turn, is part of a wider set of neoliberal values such as personal responsibility, self-improvement, self-discipline, and a growth mindset. Together, the internalisation of these neoliberal values translates into being the ‘ideal’ learner.

School

In England, there is an authoritarian emphasis on formal education with demanding expectations for data-driven outcomes. This means that an ‘ideal’ learner becomes desirable to make the education process from starting primary school to leaving secondary school as efficient as possible. In a neoliberal logic, it seemingly makes sense that to achieve this requires children to display as little emotion as possible outside the bounds of what is required for the child to be taught.

To instil self-regulation, especially in primary school age children, a significant level of external control is needed. As Jack Martin & Anne-Marie McLellan of Simon Fraser University, Canada note, pedagogues (teachers) must teach strategies to children in order to instil self-regulation techniques in primary school children.

Techniques

In relation to the Zones of Regulation, anger may be accompanied by a strategy of deep breaths or asking for a break and anxiety may be accompanied by a strategy of squeezing something such as a stress ball. Rather than endorse ways in which anger can be channelled more productively, such as through challenging unfairness, it is instead directed away to a position where it will ultimately not be dispersed, but more likely buried internally.

Regardless of the technique used, the outcome is predetermined in that the expectation is for a child to regulate emotion in order to become an efficient learner. It also creates a situation whereby self-regulation itself is regulated. Thus, self-regulation is not a freedom to self-regulate but an imposition of ideological values which must be adhered to under the illusion of self-regulation.

Dr. Manu Sharma of Thompson Rivers University in Canada notes that ultimately the complexities of self-regulation are reduced to a focus on self-control which, from a neoliberal perspective, is for the simplification of education. In other words, more efficient. This efficiency however, comes at a price of restricting children’s emotions to a very narrow range of happy, focused, calm, and content with a willingness to learn.

This is reflected by Joey Mandel who outlines what a self-regulating child looks like in the book Keep Growing: How to Encourage Students to Persevere, Overcome Setbacks, and Develop a Growth Mindset:

- Sitting up in a desk, turned toward the person who is talking.

- Listening to another person talk and hearing the words that they say.

- Playing a game (like tag) with others and controlling the body’s movements.

- Being able to read and understand the words that are on a page.

Note that things such as having a voice or dissent are completely erased in favour of a state of docility.

Responsibilisation

Of course, the source of any given emotional state will always be located within the child. As yet another of the never-ending examples of how neoliberalism always locates issues within the individual and never externally, we can see that there is no possibility that the school, the education system, or even other children could be recognised as the origin of a child’s current emotional state.

Karli Kisiel’s thesis gives an example of a child who gets tripped over deliberately by another. If the victim gets angry, cries, or shouts at the other child who tripped them over, then this is considered a dysregulated child. By doing so, it forces the child to accept responsibility for their own emotional state thus disposing of and erasing any responsibility that should have been apportioned to an external stressor.

When a child gets angry then, it is the child perceived to have a problem with an angry emotional state and not the fact that what they are experiencing is a natural reaction to an environmental stressor for example. However, whilst the above example shows a blatant stressor to which a child may react, other stressors are not so obvious.

Ideological stressors could include things such as being made to compete, perhaps in who gets the highest attendance, continual pressure to perform, or perhaps the class with the most ‘house points’. Covert stressors can wreak havoc with emotions at any age and yet any emotional reaction to them is considered ‘dysregulated’. This almost certainly creates a space within which children can be gaslighted into believing that they are at fault. It can be summed as: it is not a fault with the system, it is a fault with how you react to a fault with the system.

Further, not only is the neoliberal co-opting of the Zones of Regulation a direct attack on children’s emotional development but it is a dehumanising restriction on the range of human expression. This, in turn, can only lead to worse outcomes for children at the human level.

So, despite Kuyper’s claims that all emotions should be considered as being okay to express, and even though the Zones of Regulation may be taught in an understanding manner, the hidden message is in fact clear: there is only one emotive state acceptable for learning. Anything else equates to a dysregulated child and an inefficient ‘little neoliberal’.

References

Bradbury, A. (2019). Making little neo-liberals: The production of ideal child/learner subjectivities in primary school through choice, self-improvement and ‘growth mindsets’. Power and Education, 11(3), 309-326.

Kisiel, K. (2019). Teacher Perceptions of Effectiveness of the Zones of Regulation. Southern Connecticut State University.

Mahler, K. (2021). How Compliance-Based Approaches Damage Interoceptive Awareness & Self-Regulation – Kelly Mahler. [online] www.kelly-mahler.com. Available at: https://www.kelly-mahler.com/resources/blog/how-compliance-based-approaches-damage-interoceptive-awareness-self-regulation/

Mandel, J. (2017). Keep growing: how to encourage students to persevere, overcome setbacks, and develop a growth mindset. Markham, Ontario: Pembroke Publishers Limited.

Martin, J., & McLellan, A. M. (2008). The educational psychology of self-regulation: A conceptual and critical analysis. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 27, 433-448.

Sharma, M. (2020). Masquerade of neoliberal concepts revealed: Self-regulation skills in Ontario’s full day kindergarten program. The Canadian Journal of Action Research, 21(1), 87-101.

Very interesting to me as a non-sociologist.

After a first reading, I’m wanting a more rigorous connection between the application of the technique and producing “little neoliberals”.

I’m not seeing a deliberate intention, but rather a (potential) consequence of using the method.

If correct, however, the reduction of dissent is concerning in a state where political dissent is being criminalised, is disconcerting.

Appreciate the article for making me aware of zones of regulation being used beyond its original intent.

Thank you.

Thank you for reading.

“After a first reading, I’m wanting a more rigorous connection between the application of the technique and producing “little neoliberals””.

In all honesty, I think that could be an article in itself. The application of the zones is really part of a much wider intersecting framework of education built on a neoliberal logic.