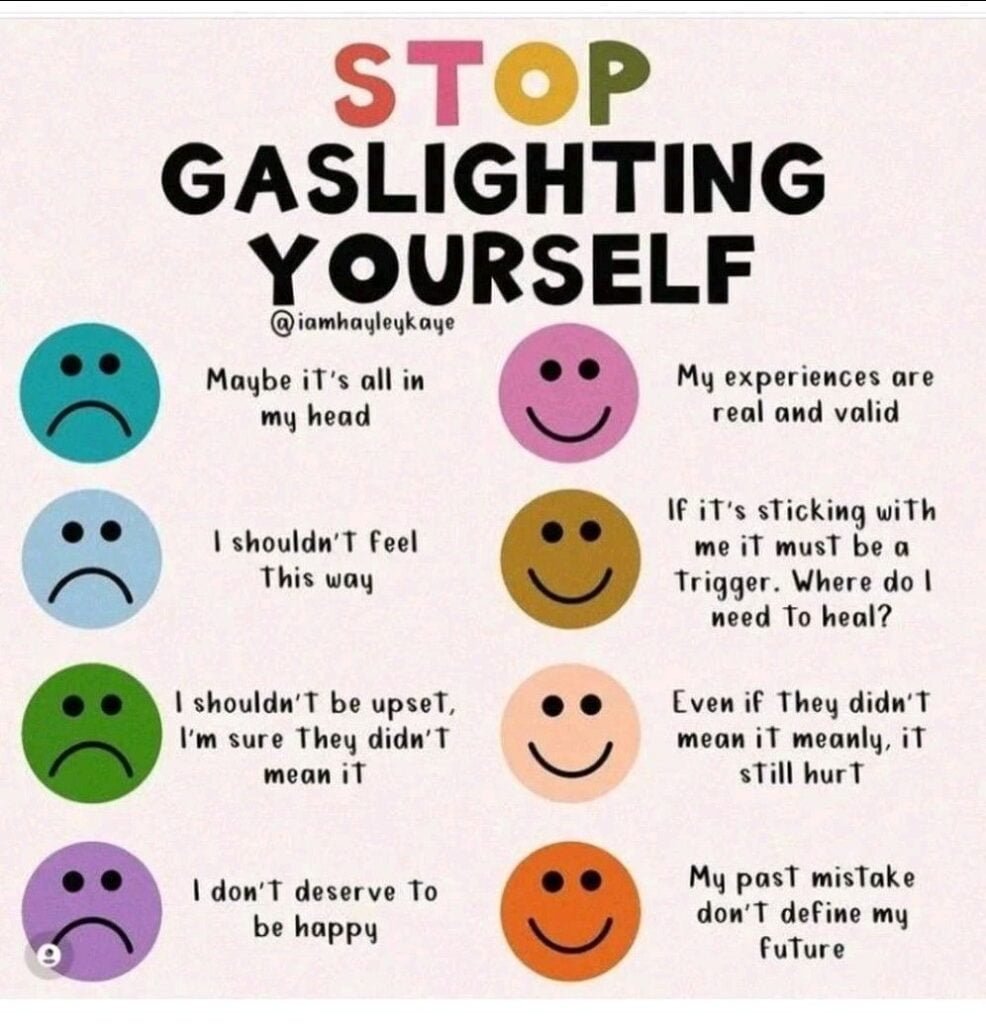

Recently, I have been noticing an increasing prevalence of articles which make claims surrounding the ‘symptoms’ of gaslighting yourself. A Daily Mail article asks “Are You Gaslighting YOURSELF? Psychologist Reveals the Three Signs You’re Self-Sabotaging…” with advice given by an experienced professional psychologist. A “medically reviewed” article from Healthline presents a breakdown of the constituent issues of self-gaslightling. Last of the three examples, is this one below from a self-described “investor in human potential & flourishing”:

What is Gaslighting?

The term ‘gaslighting’ is generally considered to have originated from the 1938 play by Patrick Hamilton called ‘Gas Light’ and additionally the identically-named 1944 film starring Ingrid Bergman. In the article ‘The Sociology of Gaslighting’, Paige Sweet describes gaslighting as “a type of psychological abuse aimed at making victims seem or feel “crazy””. Sweet, quite rightly, locates gaslighting within domestic violence situations whereby the abuser uses psychological tactics to destabilise the ‘sanity’ of the victim. Gaslighting is by no means limited to the realm of domestic violence. Other kinds of gaslighting can include concepts such as cultural gaslighting for example.

In psychology, Theodore Dorpat defines gaslighting in the following manner:

Gaslighting is a type of projective identification in which an individual (or group of individuals) attempt to influence the mental functioning of a second individual by causing the latter to doubt the validity of his or her judgments, perceptions, and/or reality testing in order that the victim will more readily submit his will and person to the victimizer.

This gives a much more definitive conceptualisation of gaslighting. Although it seems on the surface that gaslighting is an intentional act, it is also reasonable to view it as unintentional depending on the position of intent of the gaslighting perpetrator. As Rachel McKinnon explains, gaslighting can also take on an epistemological form whereby “a listener doesn’t believe, or expresses doubt about, a speaker’s testimony”. Further, it can be exemplified through the idea that a “perpetrator inappropriately privileges their own experience” of an event over and above that of the gaslit victim.

Although there a number of differing explanations as to what gaslighting is, in the context of this article, I use it to mean a situation whereby one party attempts to destabilise the psychology of another by casting doubt on the sanity, actions, or beliefs of the victim. We can see these occurrences happen on an everyday basis. For example, I once heard, although I cannot remember where, a company make the claim that it was not their products that were shrinking, but, rather, it is our hands that are growing as we age that made the product seem smaller. This is a direct attempt to gaslight consumers into accepting that they are to blame for misconceptions about the company’s product. Yet, companies reducing the size of their product is common place and is also commonly known as ‘shrinkflation’, a reduction in the size of a product to mask price rises.

Symptoms

Although this may seem comical to some, in situations of psychological violence, the symptoms can be profound. Robin Stern outlines the various symptoms of gaslighting including, but not limited to:

- You are constantly second-guessing yourself.

- You ask yourself, “Am I too sensitive?” a dozen times a day.

- You often feel confused and even crazy at work.

- You’re always apologizing

- You frequently make excuses for your partner’s behaviour to friends and family.

- You find yourself withholding information from friends and family so you don’t have to explain or make excuses.

- You know something is terribly wrong, but you can never quite express what it is, even to yourself.

- You start lying to avoid the put downs and reality twists.

- You have trouble making simple decisions.

- You feel as though you can’t do anything right.

- You wonder if you are a “good enough” girlfriend/wife/employee/ friend/daughter.

In addition to these, Rachel McKinnon argues that gaslighting can lead to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder which, given the symptoms above, seems a predictable outcome.

Gaslighting the Gaslit

As you can see from the symptoms of gaslighting described above, these are symptoms which the victim experiences psychologically from being the target of gaslighting actions. The three article examples I gave at the beginning show that these symptoms are being moved away from being the result of actions taken by a perpetrator to being actions taken by the target victim. These actions taken by the target victim are then categorised as a self-gaslighting.

To put it another way, the gaslighting behaviour of the perpetrator is claimed to become ‘internalised’ by the victim who then continues to mentally perpetuate the same gaslighting. It is no longer the psychological effects of the abusive behaviour of the gaslighter that the victim experiences, but rather the negative effects of the victim’s OWN behaviour that is then considered the source of the problem.

This claim of self-gaslighting is, in itself, an act of gaslighting.

I do not in any way suggest that this is deliberate on the part of the authors as, like I stated before, it can be an unintentional behaviour. Nevertheless, they are still unwittingly perpetuating the same gaslighting behaviour by indulging in the suggestion that it is the victim’s own psychological processes responsible for the gaslighting. In turn, if one is a victim of gaslighting, this could lead one to being convinced that they themselves are the problem rather than the abuser. Again, this is a literal reinforcing of the gaslighting that the victim has experienced.

Neoliberal Logic

The elephant in the room here is the question ‘What does this have to do with sociology’? The answer perhaps lies in the neoliberal logic of responsibilisation. This tenet of the neoliberal encourages us to take responsibility for issues that are not necessarily of our own making. Of course, when it comes to mental health, there will always be an element of having to take some self-responsibility; it is unavoidable. However, the origins of many mental health problems as being external to us are generally erased in favour of this self-responsibility and it becomes the case that ‘it is your mental health, you deal with it’!

In a similar manner then, in the rush to locate responsibility with the individual, the symptoms of gaslighting become reframed as symptoms of self-gaslighting. The extrinsic becomes invalid, and only the victim becomes responsible.

Psychologists in particular should be practicing a self-reflection to uncover hidden biases or conditioning of their own to remain critical in practice. Self-reflection is supposed to act as a defence against internalising ideological processes. However, we can add an extra layer of depth to this issue. As Carl Ratner explains in his book Neoliberal Psychology, in the neoliberal, “work and speech have been routinized and simplified to the point that they require little thinking, reflection, analysis, logic, creativity, or explanation”.

It would be highly unfair to accuse psychology practitioners of using “little thinking…or explanation”. However, as Ratner states “neoliberal psychology gives life to official, structural, policies; it informs us of the manner in which they are lived by people and the effects they have on real life”. This is equally applicable to practitioners. The policies and processes which direct practice are cut from neoliberal thinking and so it is of no surprise that an external action such as gaslighting, eventually makes its way to being a problem of the victim through discourses centred around the individual.

You Cannot Gaslight Yourself

In short, you cannot gaslight yourself. The symptoms which these articles frame as being symptoms of self-gaslighting are in fact not self-gaslighting at all. They are firmly the psychological consequences of experiencing gaslighting by an external actor. That being said, it is still important to recognise these symptoms. Unfortunately, like in many cases, the individual victim will be left to solve the problem. Framing the symptoms and experiences as being self-gaslighting is gaslighting in itself and it would be wise to reflect upon how the erasure of the external perpetrator translates into invalidating the individual’s experiences.

References

Dorpat, T.L. (1996). Gaslighting, the Double Whammy, Interrogation and Other Methods of Covert Control in Psychotherapy and Analysis. Jason Aronson, Incorporated.

McKinnon, R. (2019). Gaslighting as epistemic violence. Overcoming epistemic injustice: Social and psychological perspectives, 285-302.

Ratner, C. (2019). Neoliberal Psychology. Springer.

Stern, R. (2009). Are You Being Gaslighted? | Psychology Today. [online] www.psychologytoday.com. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/power-in-relationships/200905/are-you-being-gaslighted [Accessed 22 Jan. 2023].

Sweet, P.L. (2019). The Sociology of Gaslighting. American Sociological Review, 84(5), pp.851–875.

Further Reading

Hoggan, J. and Grania Litwin (2019). I’m right and you’re an idiot: the toxic state of public discourse and how to clean it up. Gabriola Island, Bc, Canada: New Society Publishers. (note: chapter 13)

Ratner, C. (2019). Neoliberal Psychology. Springer.

Stern, R. and Wolf, N. (2018). The gaslight effect: how to spot and survive the hidden manipulation others use to control your life. New York: Harmony Books.